Books

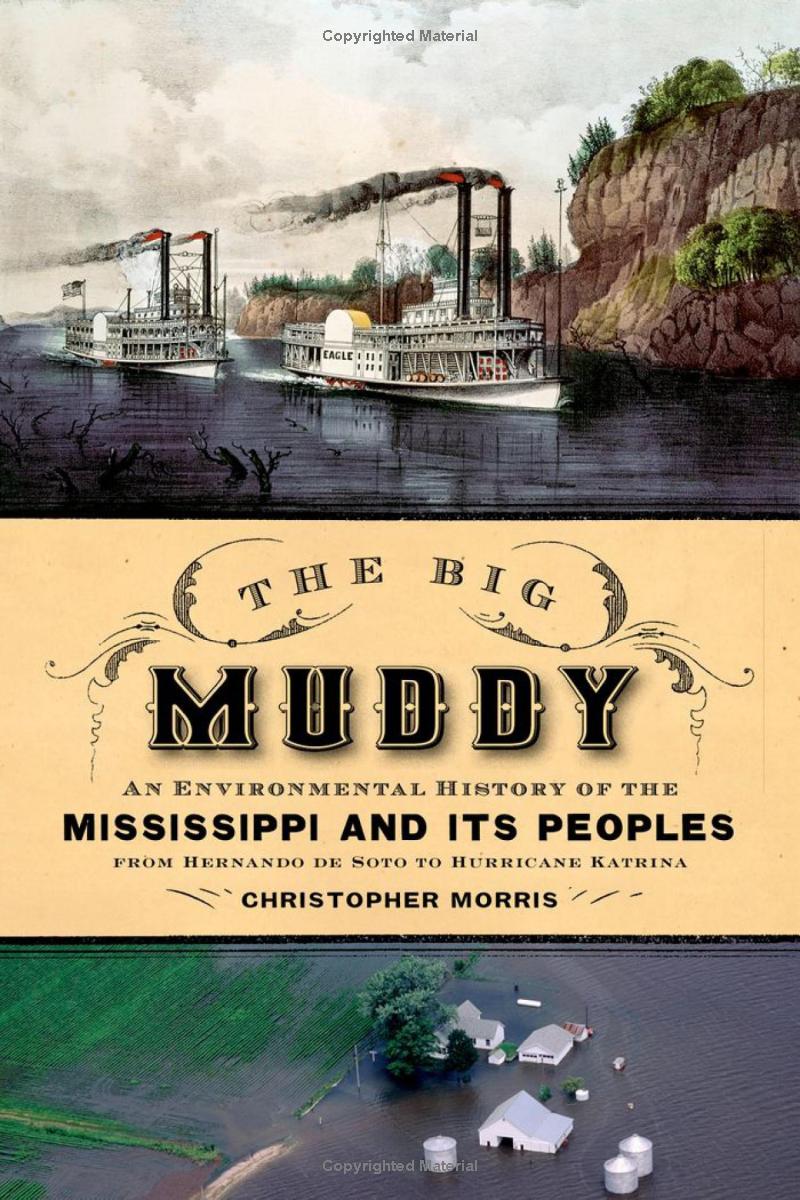

The Big Muddy: An Environmental History of the Mississippi and Its Peoples from Hernando de Soto to Hurricane Katrina

The first long-term environmental history of the Mississippi, this book spans five centuries to discuss the interaction between people and the landscape, from early hunter-gatherer bands to present-day industrial and post-industrial society. Hernando de Soto found an incredibly vast wetland. But since then, much has changed. By the 1890s, the valley was rapidly drying as a consequence of intensified human meddling--including deforestation, swamp drainage, monocropping, and most monumentally, the reconstruction of the river itself, largely under the direction of the Army Corps of Engineers—which repressed the valley’s essential wet nature. However, a repressed wet nature had a habit of returning, often in unrecognized forms, including drought, disease, and spontaneously combusting swamplands, but always, of course, by flooding. Valley residents have been paying the price for these human interventions, for the repression of the valley’s nature. And nature keeps returning with ever more damaging symptoms of its pathological condition, most visibly with the disaster that followed Hurricane Katrina.

Reviews

"What is remarkable and fresh about this scholarly study of the Mississippi in the longue duree is its comprehensiveness, density, and nuance, as well as the fresh research upon which it is based. It is a sturdy, grand, and at times stunning achievement, deeply rooted in substantial interdisciplinary research and brimming with insight."--American Historical Review

“Seven years ago this month, Hurricane Katrina triggered massive flooding in the valley of the Mississippi. The environmental backstory of the catastrophe is as rich as river sediment, and historian Christopher Morris takes us through 500 years of it. The valley's metamorphosis from vast wetland staked out by France and Spain to a patchwork of development — drained swamp,levees, deforestation, industry and poor urban planning — is powerfully recounted.” --Nature

"Elegantly written, The Big Muddy is a sweeping environmental history of a famous river told with an eye toward the relationship between water and land." --Journal of American History

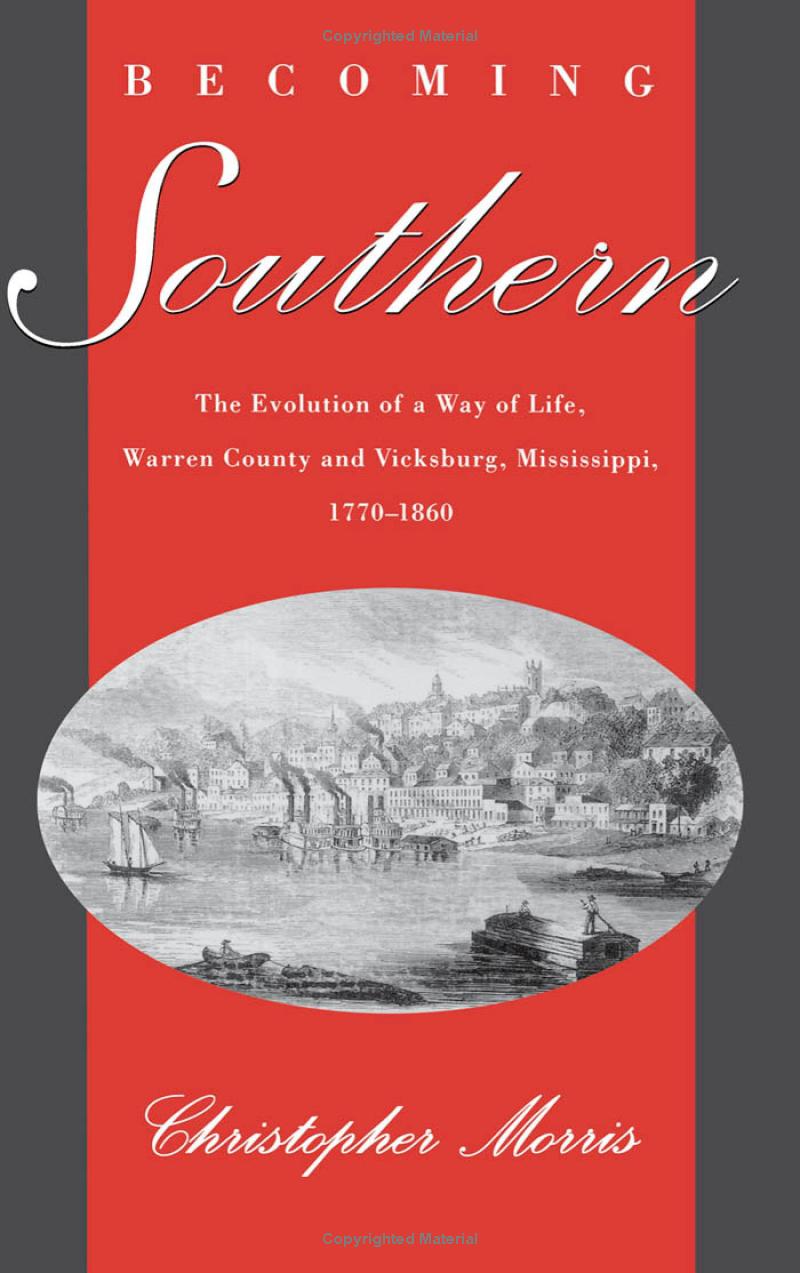

Becoming Southern: The Evolution of a Way of Life, Warren County and Vicksburg, Mississippi, 1770-1860

This study challenges the old notion of an economic and culturally static South that stood in contrast to a dynamic North and argues that the South became different from the North. At the end of the 18 th century Mississippi was socially, economically, and culturally more western than southern, having more in common with Illinois than with South Carolina. However, when men increasingly and often violently seized control over extended kin networks to acquire land and slaves, an emerging patriarchy redefined relations between masters and slaves, husbands and wives, planters and yeoman farmers, and this western place became the southern place that its white residents defended in the Civil War.

Reviews

"Christopher Morris displays the enviable ability to combine analytical sophistication and detailed analysis of local sources with a strong narrative and appropriate generalisations...[A] valuable source for students of all aspects of antebellum southern life." -- American Studies Today

"Morris's research is prodigious, his presentation captivating." --New Orleans Review

"This thoughtful, well-written study doubtless will be widely read and deservedly influential."-- American Historical Review

Featured Work

“The Environmental Humanities: Side Dish or Main Course? A Dinner Conversation.”

In this video re-enactment of a true event, several historians and literary scholars gather around the dinner table to enjoy a meal and to discuss the disciplinary and philosophical perspectives of environmental history and the environmental humanities.

“The Day Davis Cup Came to Dallas.”

This video is a documentary about the integration of Dallas City Parks and the Davis Cup tennis match between the U.S. and Mexico, played in a newly-integrated Dallas park and featuring a young Arthur Ashe on the nation’s first integrated Davis Cup team.

"How I Came to Know the Mississippi River"

We asked a diverse group of river people to respond to the prompt “How did you come to know the Mississippi River? What does it mean, to you, to know the Mississippi River?” We present below a few of the responses, in no particular order...Read more

In New Orleans, Once Again, the Irony of Southern History

Once again the entire country is confronted with the legacy of Reconstruction. It is too simple to chalk the tragedy that continues to unfold in New Orleans to the force of nature, or to an unfathomable God. Hurricanes, like earthquakes, tornadoes, eruptions, and tsunamis, do come, but who or what sends them is only half the story...Read more.

Book Chapters & Articles

"The Rise and Fall of Uncle Sam Plantation,” Charting the Plantation Landscape: Natchez to New Orleans, ed. Laura Kilcer VanHuss (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2021), 191-222.

Charting the Plantation Landscape from Natchez to New Orleans examines the hidden histories behind one of the nineteenth-century South’s most famous maps: Norman’s Chart of the Lower Mississippi River, created by surveyor Marie Adrien Persac before the Civil War and used for decades to guide the pilots of river vessels. In this collection, contributors from a variety of disciplines consider the histories that Persac’s map omitted, exploring plantations not as sites of ease and plenty, but as complex legal, political, and medical landscapes. Christopher Morris uses the famed Uncle Sam Plantation to explain how plantations have been memorialized, remembered, and preserved.

"The New History of Slavery and Capitalism: Déjà Vu All Over Again,” Journal of the Civil War Era 10 (December 2020): 524-557.

This essay compares recent studies of slavery and capitalism, their critical reception, and the social, cultural, and political context of their appearance in the early 2010s with the appearance and reception of similar studies in the 1970s.

"Mapping the Great Lakes: The Somageography of Water and Land, 1615-1828,” co-authors Robert Markley, U. of Illinois, Michael Simeone, Arizona State U., Kenton McHenry, National Center for Supercomputing Applications. Eighteenth-Century Fiction (October 2019): 169-195.

Building on our earlier computational analysis of 237 digitized maps of the Great Lakes, we use maps and accounts of Lake Huron, bookended by those of Samuel de Champlain (1616) and Henry Bayfield (1828), to explore the concept of “somageography”: how first-hand experiences with natural environments are filtered and reconfigured by map-makers, rendering maps as irreducibly complex representations of particular human and environmental conditions.

"The Canoe and the Superpixel: Image Analysis of the Changing Shorelines of Historical Maps of the Great Lakes," co-authors Robert Markley, U. of Illinois, Michael Simeone, Arizona State U., Kenton McHenry, National Center for Supercomputing Applications. Journal18: A Journal of Eighteenth-Century Art and Culture (Spring 2018), http://www.journal18.org/2619

The study of historical maps as a group or body poses interpretive challenges on a number of fronts: maps are representations of geophysical spaces, and yet they are also works of art, produced, exchanged, and viewed within the commercial and sociopolitical contexts of the cartographers’ time and culture.

"Disturbing the Mississippi: The Language of Science, Engineering, and River Restoration," Open Rivers: Rethinking the Mississippi Second Issue (Spring 2016), online at http://editions.lib.umn.edu/openrivers/.

From top to bottom, projects aimed at restoring the Mississippi River are underway in both deed and word. In the area of the Twin Cities, the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers is dredging pools along the floodplain and using the sediment to construct islands and restore wetland fish and waterfowl habitat...Read more

"Reckoning with ‘The Crookedest River in the World’: The Maps of Harold Norman Fisk,"Southern Quarterly Special Issue on the Mississippi River as Twentieth-Century Southern Icon 52 (Spring 2015): 30-44.

History, science, and art in Harold Norman Fisk's maps of the Mississippi River. Fisk's mid-twentieth-century maps were intended to lend highly technical support for a plan by the US Army Corps of Engineers to straighten the Mississippi River with a series of cut-offs. Today, Fisk's maps are (mis)read as beautiful reminders of why engineers should leave the river alone.

"Wetland Colonies: Louisiana, Guangzhou, Pondicherry, and Senegal," in Cultivating the Colonies: Colonial States and their Environmental Legacies, edited by Christina Folke Ax, Niels Brimnes, Niklas Thode Jensen, and Karen Oslund (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2011), 135-163.

In 1715 and 1716 Antoine Crozat, director of the French colony of Louisiana, drafted several reports for his investors in France, in which he described the natural environment of the lower Mississippi Valley, detailing its prospects for profitable enterprise and trade...Read more

"The Articulation of Two Worlds: The Master-Slave Relationship Reconsidered," Journal of American History 85 (December 1998), 982-1007.

In 1830 or thereabouts Edmond Covington concluded that his hilly mississippi was not well suited to cultivating cotton. He therefore turned his plantation into what he deescribed as a "slave breeding" business, not primarily with the intention of selling slaves, but to increase the capital holdings and assets of the plantation...Read more.